What is this book summary about?

This is the summary of Service Design – from insight to implementation by Andy Polaine. It is a truly great book and you’ll find the most interesting parts of it below.

Even though it may be obvious what differs a service from a product I found stuff in this book that sparked my imagination. I would say that Service Design is almost like a handbook for service designer. Of course, that is a good thing if you intend to design services. And almost all of us are nowadays.

The service economy is all around us, and that is why this book should be useful for almost everyone. For me who´s in digital advertising, it will be. I like to see my work as planning and tweaking services to enhance value for the user and the provider. The summary of Service Design includes a quite detailed process of doing so, just like the title says.

And there is a big value in understanding the whole process from beginning to end since you can pick the parts that are applicable to your purpose and customize them to your needs. You can’t just copy the process straight off from the book, but you can use the content as a backbone to build your stuff on. For that purpose, the summary of Service Design is worth gold.

Download the Summary of Service Design

Click the button below to download the summary of Service Design – From Insight to Implementation.

More about the book

Here’s a link to Service Design – from insight to implementation website. Also make sure you stop by the author Andy Polaine´s blog if you haven’t already. It isn’t updated very often but I found a couple of good reads there. One website that you definitely shouldn’t miss is Service Design Tools. This is the perfect extension of the book holding an open collection of communication tools for service design.

Amazon´s description of Service Design

We have unsatisfactory experiences when we use banks, buses, health services and insurance companies. They don’t make us feel happier or richer. Why are they not designed as well as the products we love to use such as an Apple iPod or a BMW? The ‘developed’ world has moved beyond the industrial mindset of products and the majority of ‘products’ that we encounter are actually parts of a larger service network.

These services comprise people, technology, places, time and objects that form the entire service experience. In most cases some of the touchpoints are designed, but in many situations the service as a complete ecology just “happens” and is not consciously designed at all, which is why they don’t feel like iPods or BMWs. One of the goals of service design is to redress this imbalance and to design services that have the same appeal and experience as the products we love, whether it is buying insurance, going on holiday, filling in a tax return, or having a heart transplant.

Another important aspect of service design is its potential for design innovation and intervention in the big issues facing us, such as transport, sustainability, government, finance, communications and healthcare. Given that we live in a service and information age, a practical, thoughtful book about how to design better services is urgently needed.

Read the Summary of Service Design

Summary of Service Design | Chapter 1: Insurance Is a Service, Not a Product

Product vs. service:

– When customers buy a physical product, they can inspect it for build quality, flaws, or damage. It is much harder to do that with services, especially ones that are essentially a contract based on the chance of a future event.

– Unlike products, which have physical affordances signaling their potential usage, services can be abstract or even invisible.

– Products require designers to deal with many moving parts, but services require us to

design systems that adapt well to constantly changing parts. Networks, organizations, and technology evolve on a daily basis, but the service still needs to deliver a robust customer experience.

Quantitative methods: Quantitative methods are good for creating knowledge and understanding the field, but they are not very useful for translating knowledge into action and helping organizations do something with it. Qualitative studies are very good at bridging this gap.

Option vs. choice: they do not want to have to choose from lots of options, but they want the

experience of having made their own choice.

Genuine personal: When it comes to customer relations, people see straight through things

that are meant to be personal but actually are not. There is only one type of personal, and it is to be genuinely personal.

Summary of Service Design | Chapter 2: The Nature of Service Design

Network thinking: Service design grows out of a digitally native generation professionally

bred on network thinking. Our focus has moved from efficient production to lean consumption, and the value set has moved from standard of living to quality of life. When we make smart use of networks of technology and people, we can simplify complex services and make them more powerful for the customer.

How to create a service: When we build resilience into the design, services will adapt better

to change and perform longer for the user. When we apply design consistency to all elements of a service, the human experience will be fulfilling and satisfying. When we measure service performance in the right way, we can prove that service design results in more effective employment of resources—human, capital, and natural.

Service mindset: Applying the same mindset to designing a service as to the design of a product can lead to customer-hostile rather than user-friendly results.

Products are discrete objects: because the companies that make, market, and sell products

tend to be separated into departments that specialize in one function and have a vertical chain of command—they operate in silos. The division of the silos makes sense to the business units, but makes no sense to the customer, who sees the entire offering as one experience.

Holistic experience: Often, each bit of the service is well designed, but the service itself hasn’t been designed. The problem is that customers don’t just care about individual touch points. They experience services in totality and base their judgment on how well everything works together to provide them with value.

Interactions, motivations and behaviors: The industrial legacy of treating services like

products means that services often underperform and disappoint because they cannot be fixed in the same way as problems with products. Services are about interactions between people, and their motivations and behaviors. Understanding people is at the heart of service design.

Value only when using a service: A fundamental characteristic of services is that they create value only when we use them. Ex: An empty seat on the train has no value once it has left the station. Even at the dentist’s office, nothing will happen unless the patient opens her mouth and tells the dentist where it hurts. Product-oriented organizations often fail to see the potential of using their customers to make a service more effective.

Users are co-producers: Services are co-produced between the provider and users. The

biggest missed opportunity in development is that organizations don’t think about their customers as valuable, productive assets in the delivery of a service, but as anonymous consumers of products. Most customers have a keen interest in getting as much as possible out of the services they use, and by enabling users to step in and co-produce, providers can create win-win solutions.

Why service design: The combination of enterprise systems that store and link vast amounts

of data with mass-consumer access to data through the Web and mobile telephony is transforming the way people live their daily lives. At the same time, the quality of service often suffers due to the complexity of linking these systems together in a way that makes sense to customers. This combination of opportunities and problems is the reason why service design has emerged as a specific design approach.

Service design as competitive advantage: To an increasing degree, we also see that the

design of services is becoming a key competitive advantage. Physical elements and technology can easily be copied, but service experiences are rooted in company culture and are much harder to replicate. People choose to use the services that they feel give them the best experience for their money, whether they fly low-cost airlines or spend their money on a first-class experience. Some of the greatest opportunities are found where a business model can be changed from a product model to a service model.

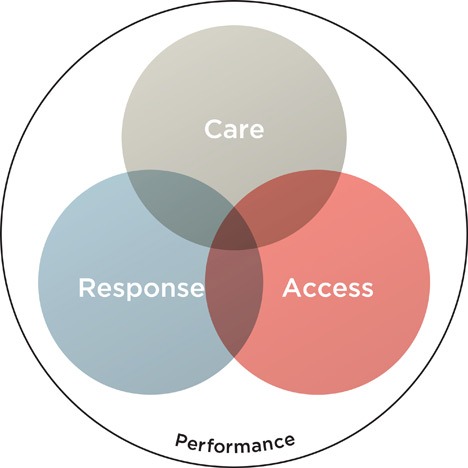

The three core values of services: care, access, and response. Most services provide customers with at least one of these or, often, a mix of all three.

Care for an object: a car, an air-conditioning system, a wool coat—is provided by auto mechanics, HVAC technicians, or dry cleaners. Care for a person is provided by a wide range of services, from nurseries to nursing homes. Accountants, lawyers, and therapists provide care for money, freedom, and happiness.

Access: Generally, the services for which access is the primary value are services that give

people access to large, complex, or expensive things that they could not obtain on their own.

These services are often a fundamental part of people’s lives that are typically noticed only

when they are disrupted, such as when the daily commuter train is canceled, or when schools are closed due to heavy snow. People expect the infrastructure to always be there for them. As individuals, we understand that we all have our own experiences of the specific access we have to this infrastructure—this is the service layer that enables us to access our bit of the larger whole.

Response: The third category is services that respond to people’s (often unforeseen) needs.

These services are usually a mix of people and things that are able to assist us: an ambulance rushing to an accident, a teacher helping a child with a math problem, or a store assistant finding a customer a pair of jeans with the right fit. In many respects, response is the default understanding of what service is—think of a waiter responding to a request for a glass of water, for example. Service is someone doing what he or she has been asked to do. In this sense, response services are fundamentally different from products in that they are not predesigned but created in the moment in reaction to a request.

Behind the scenes: It is because many services are almost invisible that nobody takes care to design them. As a result, service designers frequently need to make the invisible visible by showing customers what has gone on behind the scenes, showing staff what is happening in the lives of customers, and showing everyone the resource usage that is hidden away.

Performance of service: The point of difference for any specific service is how it is delivered. We think of this as the performance of the service. Performance, as we understand the word

from music or theater, means the style or the way in which the service is delivered. This

performance makes up the immediate experiences that service users have. This “experience” aspect of performance is the delivery of the service to the service user on the “front stage.”

Performance of value: the other meaning of the word “performance,” equally useful to

service design, is service performance as a measure of value. How well is the service performing? This measure is both outward and inward facing. Outward-facing value measurement asks how well the service is achieving the results promised to the service users.

For example, how often does a hip operation result in a 100% recovery? Inward-facing value

measurement examines how well the service is performing for the organization. For example, how cost effectively is it delivering hip operations? This value aspect of performance is the “backstage” measure of the service by the business—all the things that happen behind the scenes that help create or run the service experience for customers but that they don’t see.

Summary of Service Design | Chapter 3: Understanding People and Relationships

Service as relationship: People don’t “use” a healthcare professional or a lawyer, and they

don’t consume a train journey or a stay at a hotel. Instead, people enter into a relationship

with professionals and service providers. It is essential to understand that services are, at the very least, relationships between providers and customers, and more generally, that they are highly complicated networks of relationships between people inside and outside the service organization. The staff who interacts with customers is also users and providers of internal services.

Focusing on individuals: As soon as we forget that people—living, feeling, emotive human

beings—are involved throughout the entire chain of events, not just at the moment of use by

the customer, things go wrong. Understanding not just people as individuals but also the

relationships they have to others is essential to understanding how a service might operate.

Shifting attention from the masses to the individual enables radical new opportunities, and

because of this fact, service design places more emphasis on qualitative over quantitative research methods. Statistics are not very actionable for designers—we need to know the

underlying reasons.

Research: The purpose of the research is to generate insight about needs and behaviors that can lay a solid foundation for a productive project and robust ideas, and to confirm these by prototyping early and often to test them out.

Service design and innovation: Service design and innovation go hand in hand. Much of the

work involves shifting clients from an industrial mindset to thinking in a service paradigm. In the end, insights that drive innovation confidently answer the question: “Will our offering make sense in the context of people’s lives, and will they find it valuable?” Many service design projects are about improving an existing service, and here the insights research focus is improving an existing service, and here the insights research focus is slightly different. If a service already has many customers, and competitors have entered the market, one can assume that people understand how the service is used and that it is of value. In these cases, the focus is on discovering points of failure in the service (known in service design jargon simply as “fail points”) and opportunities for enhancing the experience. This focus means that we can narrow the research scope and look less at unfulfilled needs and more at usage in context.

Co-designing: Service design is about designing with people and not just for them, and it is

here that it differs from classic user-centered design and much of marketing. “People” does not just mean customers or users, it also means the people working to provide the service, often called frontline, front-of-house, or customer-facing staff. Their experience, both in terms of their knowledge and their engagement in the job, is important to the ongoing success of a service for two key reasons:

- Happy staff equals happy customers, so their inclusion in the design of services ensures that providing the service will be a positive experience. Staff who are involved in the creation and improvement of service not only feel more engaged but through learning about the complex ecology of the service they provide and how to make use of innovation tools and methods, they are also able to continually improve the service themselves.

- Along with customers, frontline staff is often the real experts. They provide insights

into the potential for service design that are frequently as valuable to the project as

insights from customers, and they can provide a perspective on the day-to-day

experiences that managers and marketing people may never experience.

Segmentation by Journey Stage versus Target Groups: In our definition of service design, we talk about experiences that happen over time. In product design or marketing research, we would typically segment the market and interview people in different age, socioeconomic, or behavioral groups. In services, a more useful way to engage with people is by looking at different stages of their relationship with the service. This strategy allows us to

research the different journeys people might take through a service and how they transition

through the various touch points.

Researching across Multiple Touch points: people interact with services through different

channels in different situations that often include interactions with other people. Context is critical to gathering insights into people’s interactions with touch points, and a lab is not a context in which this can happen. From a service point of view, we are really after understanding how different touch points work together to form a complete experience. Therefore, try to do research with people in the situations where they use the service.

Gap between expectation and experience: What is most important to look for is variation in quality between the touch points and the gap between expectations and experiences. When

people get what they expect, they feel that the quality is right. Whether it is a premium or a

low-cost service, a minimal gap between expectation and experience means greater customer satisfaction.

Summary of Service Design | Chapter 4: Turning Research into Insight and Action

Level of insight: The process is always the age-old trade-off between time, money, and quality. A useful way to think about this is to have a menu of low, middle, and high levels of detail (and effort) to draw from as the situation requires.

Low: The low granularity of analysis is basically a summary of what a small sample of around four or five research participants say in relatively short depth interviews (say, 45 minutes), and does not include any other activities, such as in-person observation, workshops, site visits, or testing.

Middle: The middle level of analysis provides deeper and more crafted insights based on research with around 10 participants.

High: The output provides top insights plus a summary, but is more in-depth than the low level of analysis. This middle level also prioritizes issues for the project, which are produced from an internal workshop with the client that is conducted by the service design agency. The insights findings may be presented as a written report, presentation slides, a blog, or summary board.

Depth interviews: focus groups are structurally problematic because each member gets only

a few minutes to speak and even these short interactions are influenced by social pressures. In contrast, in-depth interviews offer deeper insights and are better value for the money. Interviewees should never be corrected about something they are explaining, even if they are completely wrong. Instead, ask them how or why they know what they are saying; it will reveal a lot more.

Interviewing in pairs: In one-to-one situations, consumers in particular may say what they

think you want to hear. For this reason, we find consumer research interviews conducted with couples or pairs of friends can be more useful than interviews with individuals because the subjects feed off each other’s answers and build on them. If they know each other well, they are likely to feel more comfortable and give genuine answers. We have found that pairs provide the most truthful feedback, and of course, you get two people’s opinions in the same time it takes to interview one person.

Preparing: Below is a general overview of the process that we usually follow.

- Recruit: This step can take two to three weeks, so it should be started early. If possible, use a recruitment company to do the hard work of recruiting interviewees. This may seem expensive but saves a lot of time. You need to be as clear as possible with the recruiters about who you need.

- Research: You may not know much about the topic you are interviewing on. If this is the case, you may need to research the area, but don’t spend too much time on it. Sometimes it is best to be a little naïve because it prevents you from making assumptions;

- Plan the topics: When you have found out more, construct a prompt card. This should be a list of topics you want to cover during the interview.

Participant observation: Participant observation, or shadowing, provides rich, in-depth, and accurate insights into how people use products, processes, and procedures. It is very useful for understanding context, behavior, motivations, interactions, and the reality of what people do, rather than what they say they do. It gives good depth and insight into latent needs—the things people actually need, but perhaps do not know that they need because they are so used to their old routine.

It is essential with this type of research to carry out the observations in the participant’s natural environment. When observing, there are two approaches you can take: the fly-on-the-wall method in which you just observe and pretend not to be there, or a more active approach in which you interact with users by asking them questions about what they are doing.

Service safari: A service safari gives participants—usually members of the project team from

the client side—firsthand experience of other (sometimes seemingly unrelated) services. Participants use these other services for a few hours or even a day. Some of the services to be explored should be outside the client’s own industry, which enables participants to be more objective about how the services they experience are delivered. This experience may provide ideas that they can transfer back to their own business.

Tassi’s Service Design Tools website: www.servicedesigntools.org

Diaries: Diaries often reveal more intimate thoughts and feelings about people’s lives—more than they might tell you in an interview.

Insight boards: Insights boards can be used to present insights based on real people who

have been interviewed as an alternative to using fabricated personas. It is important to include photographs on each board to help people relate to the participant. The boards should be able to be read at three levels: a headline quote, a series of key insights (backed up with quotes), and a larger paragraph of narrative text.

Summary of Service Design | Chapter 5: Describing the Service Ecology

Service ecology: it is sometimes necessary to gain a sense of the context in which the service is operating, which is usually complex. You can map this out in a service ecology—a diagram of all the actors affected by a service and the relationships between them, displayed in a systematic manner. Looking at services as ecologies also emphasizes the point that all of the actors in a service exchange some sort of value. A healthy ecology is one in which everyone benefits, rather than having the value flow in one direction only.

The basic actors in a service ecology: are the enterprises that make a promise to the customer (or service user), the agents who deliver that promise through different channels, and the customers who return value back to the enterprise. The enterprise itself does not deliver experiences and utility to people, however. These are provided by the agents who are in direct contact with users through channels and touch points. Channels are the overall medium, such as e-mail, telephone, and face-to-face, and a touch point is an individual moment of interaction within that channel, such as a single call or an e-mail exchange. So, a customer might interact with several touch points across a single channel or across many channels. The role of the enterprise is to deliver the tools and infrastructure that agents need to deliver a good service experience.

Brand value: Customers are usually motivated to provide labor, knowledge, and data if these will help them get a better result, and when customers invest in the outcome, they connect more strongly to the brand.

The promise to the customer: Is fulfilled when agents provide utility and experience to

customers through activities across the various channels, known as “front stage” in service design (see “The Service Blueprint” below). Customers return added value to the enterprise

through cooperation, information, and feedback, along with payment for services. If you provide users and staff with a good “stage” on which to interact, and give them well-defined roles, clear goals, and the necessary props, people are likely to make the most out of the situation and create great experiences together.

The service ecology map has three main purposes:

– To map service actors and stakeholders

– To investigate relationships that are part of or affect the service

– To generate new service concepts by reorganizing how actors work together

Boxes versus Arrows—Finding the Invisible Connections: Arrows and lines in organizational charts and process diagrams often represent time, context, and connections.

The problem is that arrows and connecting lines are so ubiquitous in diagrams that they are ignored. It is much easier to focus design effort on the boxes because they represent tangible touch points—the website, the ticket machine, and so on—but most people forget to think about designing the experience of the arrows, which are the transitions from one touch point to the next. Yet these connections contain some of the most important elements of positive experiences because they signify movement in time and space. It is as if companies spend fortunes building gleaming towers and cities while the roads between them are muddy dirt tracks. If the connections (the arrows connecting the channels) are ignored, the silos are still potentially there, but they are just arranged in a circle.

Interactions: All experiences of a service are a result of interactions of some kind. Obvious

interactions are various touch points such as objects, interfaces, and interpersonal interactions. Less obvious are interactions between previous experiences or beliefs.

Time and place: Service experiences are also affected by the contexts of time and place, and the most amazing thing at the wrong time can be more of a service design failure than something average that is delivered at exactly the right moment. Some of the best service

experiences are like the ideal wine waiter—there when he is needed, but somehow invisible when he is not.

From Ecology Map to Service Blueprint : The service ecology map gives us the bird’s-eye

view of the ecosystem a service exists within, and the insights research gives us the bottomup view from the stakeholders.

The service blueprint: A classic example is a hotel stay—guests do not often see the activities of the staff who clean and make up the rooms (backstage), just the results (front stage). Often, this backstage activity is evidenced in some way by bringing it front stage, such as the folded toilet paper tip in a hotel bathroom that indicates the room has been cleaned.

A service blueprint is a map of:

– The user journey—phase by phase, step by step

– The touch points—channel by channel, touch point by touch point

– The backstage processes—stakeholder by stakeholder, action by action

Blueprint vs. service ecology: The blueprint is different from the service ecology in that it

includes specific detail about the elements, experiences, and delivery within the service itself, whereas the service ecology diagrams the service at a much higher level and shows the entire service’s relationship to other services and the surrounding environment in which it operates.

Blueprints for Analysis of an Existing Service: The service blueprint maps how the service is constructed, connecting all the channels and touch points to the customer journey and the backstage processes that are required to deliver them. It gives service designers a platform to systematically test people’s different journeys through the system. You can track their path across time and touch points, and reveal where real value was created and where

opportunities were wasted.

The service life cycle: the first step in creating a blueprint is to establish the stages of the

service experience over time—the service life cycle—and then add the roles of the people involved in the service (usually starting with the customer or service user) and the touch

point channels.

Blueprint categories:

– Aware: The point when the user first learns about the service

– Join: The sign-up or registration phase

– Use: The usual usage period of the service

– Develop: The user’s expanding usage of the service

– Leave: The point when the user finishes using the service, either for a single session

or forever

A complete experience: think through how all the touch points connect together as a complete experience.

Summary of Service Design | Chapter 6: Developing the Service Proposition

The service proposition: is essentially the business proposition, but seen from both the

business and the customer/user perspective. The service proposition needs to be based on real insights garnered from the research. For example, is there an unmet need, a gap in the market, an underdeveloped market, a new technology that disrupts existing models, an overly complicated service infrastructure that can be radically simplified, or a changing

environment?

Zooming: The way to manage zooming in and out, from detail to big picture, is to use the

service blueprint as a space in which different scenarios can be played out. The blueprint

should show the essential parts of the service ecology so that you can track different user

journeys through it in a number of “What if?” scenarios.

Mix of channels: Typically, most users will experience a mix of channels and may switch

between them depending on their context—at work, at home, while traveling, and so on.

Individual touch points: An individual touch point is the intersection of time—the phase or

step in the journey—with a channel, such as a customer signing up for a service using a form on a website.

The purpose of service design blueprinting: is to ensure that all the different elements

across all touch points are not designed in isolation. The blueprint leads to the design specifications for each touch point and acts as a way to orchestrate them all. Service design is both broad and deep.

Summary of Service Design | Chapter 7: Prototyping Service Experiences

Service experiences: Working with experiences is to service design what working with communications is to graphic design. The current and future experiences of people — customers, clients, users, patients, consumers—are the context in which service design works. Services can be promoted through positive experiences by ensuring that they meet or exceed users’ expectations.

Types of Experience

– User experience: interactions with technologies

– Customer experience: experiences with retail brands

– Service provider experience: what it is like on the other side

– Human experience: the emotional effect of services (e.g., healthcare) that impact quality of life and well-being.

Customer experience: The customer experience is the total sum of a customer’s interactions

with a service. In many respects, the management of customer experience is about managing the delivery of the service and customer expectations against what is actually delivered. As customers, we have expectations of a service in terms of quality and value that overarch the day-to-day tasks we undertake.

These expectations are set by the brand and our experience of other services, and are closely tied to the amount we are paying. Consider budget airlines compared to premium air travel—the brand promise of each sets our service expectations. If our experience does not match our expectations, we are disappointed and become more likely to switch next time.

In this case, the emotion of bad service is not just frustration but also a reflection on the quality we are getting for our money. We might hate the service on a budget flight (most people do), but it is exactly what we were promised when we booked the cheap ticket.

Culture: Quality of service tends to be part of a company’s culture, and culture is much harder to restructure once it has been set.

Product experience: Product experience is about the quality of tangibility. The fundamental

concept to embrace when you design a service is that perceived quality is defined by the gap between what people expect and what they actually experience.

Therefore, the primary focus for a service designer is to make sure that every interaction with the service sets the right level of expectation for the next interaction. It means that the level of quality and the nature of the experience need to be the same over time and across touch points.

Quality and experience: when you exceed expectations at a certain point, you have already

set yourself up to disappoint at the next interaction if you cannot deliver at the same level. Sometimes, you may need to consider reducing the quality of a certain touch point to enhance the overall experience of quality in the service. When you set consistent expectations in each interaction and fulfill them in the next, people will feel quality.

Consistency: Customers choose their own speed and path through a service, so you can only minimize the gap between expectation and experience by securing consistency.

Orchestration: Great service experiences happen when all touch points play in harmony, and

when people get what they expect day after day.

Prototyping: Unlike a product prototype, which is an object people can hold in their hands

to get a sense of how it feels, service prototypes need to be experiences of interacting with multiple touch points as well as taking into account how those experiences unfold over time

and in context.

When prototyping, ask yourself:

1. Do people understand the service—what the new service is or does?

2. Do people see the value of the service in their life?

3. Do people understand how to use it?

4. Which touch points are central to providing the service?

5. Are the visual elements of the service working?

6. Does the language and terminology work?

7. Which ideas do the experience prototype testers have for improvement?

Customer journey: Develop one or more customer journeys that describe the situations you

would like to act out with customers. The user journey acts as the manuscript for the prototype and should describe the different actors and which tangibles are needed.

Summary of Service Design | Chapter 8: Measuring Services

Consumption as measurement: Measuring efficiencies in production makes sense from an

industrial point of view, although the sustainability agenda requires companies to consider

the full life cycle of products. But for services, what must be measured is consumption—the

experiences of the service provider’s agents and users. When you base measurement on the problems and successes people have when they use a service, you are better positioned to streamline delivery while improving the customer experience.

Services for a shared culture: Ultimately, what is measured should be driven by what is

most likely to create a shared culture of improvement within the organization. This is what

creates valuable, long-term relationships with customers and enables sustainable growth.

Behaviors in service design: Some typical behaviors often addressed in service design projects can be translated to results on the bottom line:

– New sales: increased acquisition of new customers

– Longer use: increased loyalty and retention of customers

– More use: increase in revenue for every customer

– More sales: increased sales of other services from the same provider

– More self-service: reduced costs

– Better delivery processes: reduced costs

– Better quality: increased value for money and competitiveness

SERVQUAL : a service quality framework called SERVQUAL. It was created as a method to

manage service quality by measuring gaps between what organizations intend to deliver and

what they actually deliver, as well as between people’s expectations and their actual experiences with a service.

RATER: a service quality framework that measures gaps between people’s expectations and

experience along five key dimensions:

– Reliability: the organization’s ability to perform the service dependably and accurately

– Assurance: employees’ knowledge and ability to inspire trust and confidence

– Tangibles: appearance of physical facilities, equipment, personnel, and communication materials

– Empathy: understanding of customers and acknowledging their needs

– Responsiveness: willingness to help customers, provide prompt service, and solve problems

The Triple Bottom Line: The basic concept of the triple bottom line is that an organization

should be measured not only by its financial performance, but also by the ecological and social outcomes of what it produces. The model challenges the idea that companies are responsible to their shareholders only, and states that organizations are responsible to their stakeholders—anyone who is directly or indirectly affected by the actions of an organization.

Summary of Service Design | Chapter 9: The Challenges Facing Service Design

Things vs. benefits: Service design has a role to play in shifting economies away from valuing things to valuing benefits, because what is required for this shift is behavior change in two key audiences: organizations need to shift their offers, economics, and operations to orientate around providing access and convenience rather than products alone; and customers need to shift their purchasing decisions from ownership to access and convenience.

Experience instead of the product: What we actually need is the experience or utility—to get from point A to point B, to watch a film, or to make a hole in the wall—not the product. For a

service to replace a product, it must be tangible, useful, and desirable, and service design

provides an approach to designing these services.

Services in networks: Services that use networks to connect people act as multipliers to these individual shifts in resource usage and can reflect the effect of those multiplied changes back to people in ways that inspire further shifts in behavior.